by Natan Kaziev

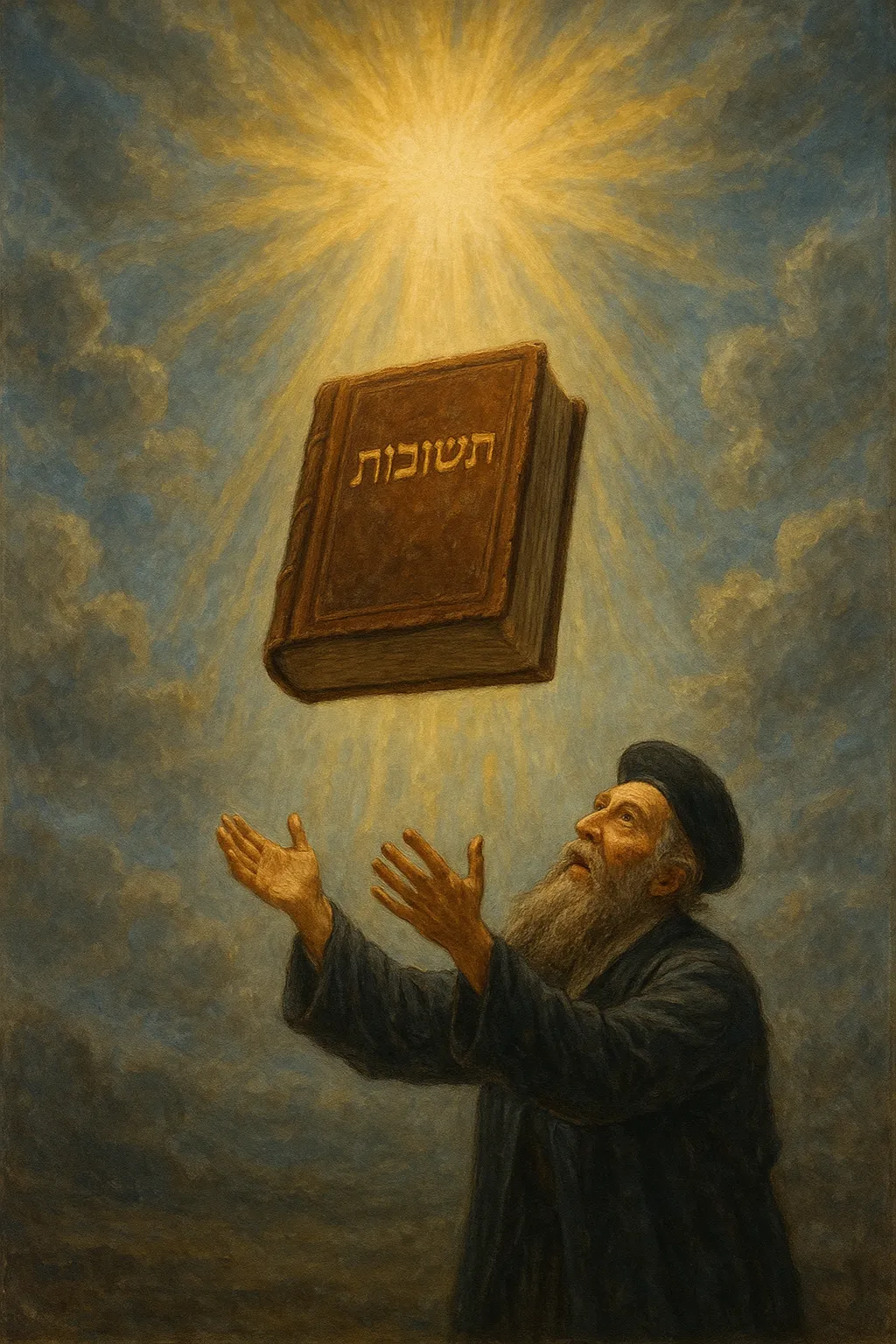

She'elot Utshuvot Min Hashamayim: Rabbenu Yaakov of Marvège

She'elot Utshuvot Min Hashamayim

Rabbenu Yaakov of Marvège

שְׁאֵלוֹת וּתְשׁוּבוֹת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם

The story of the tshuvot that Rabbenu Yaakov of Marvège received from heaven

And how Poskim deal with such tshuvot

(THE HALACHIC DISCUSSIONS IN THIS ARTICLE ARE NOT MEANT AS PRACTICAL HALACHIC RULINGS)

History

She’elot Utshuvot Min Hashamayim (שׁוּ"ת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם) was written by one of the rishonim[1], Rabbenu Yaakov of Marvège (Marvejols), France. He was one of the בַּעֲלֵי הַתּוֹסָפוֹת [2] and lived in the beginning of the 13th century.

Methodology

This sefer– unlike the sefarim of most rishonim– was written purely based on the pesakim (rulings) given to Rabbenu Yaakov through a “שְׁאֵלַת חֲלוֹם”-- a question asked from heaven through a dream.

This is described by the Radvaz (Rabbenu David ben Zimra) as follows (in the context of defending the minhag of saying פִּיּוּטִים [liturgical poems] in chazarat hashatz):

"וְכֵן יֵשׁ בְּיָדַי קְצָת שְׁאֵלוֹת שֶׁשָּׁאַל אֶחָד מִן הָרִאשׁוֹנִים מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם עַל יְדֵי הִתְבּוֹדְדוּת וּתְפִלָּה וְהַזְכָּרַת שֵׁמוֹת וְהָיוּ מְשִׁיבִין לוֹ עַל שְׁאֵלוֹתָיו וְשָׁאַל עַל זֶה גַּם כֵּן וְהֵשִׁיבוּ לוֹ שֶׁמֻּתָּר."

“I have in my possession some questions that one of the rishonim asked from heaven through solitude and tefillah and use of divine names, and they would answer him on his questions, and he asked on this too (saying פִּיּוּטִים), and they answered him that it’s permitted.”

Examples of rulings of שׁוּ"ת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם, and Debates in Poskim about using his rulings

We will go through one of the cases where the poskim (halachic decisors) discuss the rulings of שׁוּ"ת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם, and see how they deal with this sefer and to what extent they accept his methodology.

The Chida in Birkei Yosef (Orach Chaim 654:2) and Yosef Ometz (siman 82) says that he saw in Eretz Yisrael that there were women who were making a bracha on the mitzva of lulav, despite Maran in Shulchan Aruch saying that it’s a bracha levatala. He says that he originally assumed that it was an incorrect minhag, and that the “חכמים זקני דורנו” (elder sages of his generation) said that that it was a מנהג טעות (a mistaken practice). However, he later found that this halacha was already discussed in שׁוּ"ת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם, who rules in accordance with the practice to make a bracha in this case. Due to the ruling of שׁוּ"ת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם, the Chida ruled that women make this bracha. (The words of the Chida are quoted by the Kaf HaChayim Orach Chayim 17:4, although it seems that he doesn’t actually decide in favor of the Chida unless there’s a minhag to make the bracha.)

These are the words of שׁוּ"ת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם, siman 1:[4]

שאלתי על הנשים שמברכות על הלולב ועל מי שמברך להם על תקיעת שופר, אם יש עבירה בדבר ואם הוי' ברכה לבטלה אחרי שאינן מצוות ואם לאו:

I asked about the women who make a bracha on the lulav, and about one who makes a bracha for them on teki’at shofar (shofar blowing), if there is an avera (sin) in this matter, and if it is a blessing in vain, since they aren’t commanded (in these mitzvot) or not?

והשיבו וכי אכשורי דרי כל אשר תאמר אליך שרה שמע בקולה, ולך אמור להם שובו לכם לאהליכם, וברכו את אלהיכם, והעד נר חנוכה ומגילה, ופרשו לי מה מצינו במגילה וחנוכה מאחר שהיו באותו הנס חייבות בהם ומברכות עליהם, ובלולב נמי מצינו סמך לדבר שאין לו אלא לב אחד לאביו שבשמים, גם בשופר מצינו דאמרינן שאמר הקב"ה אמרו לפני מלכיות שתמליכוני עליכם, זכרונות שיבא זכרון אבותיכם לפני לטובה, ובמה בשופר, והנשים נמי צריכות שיבוא זכרונותיהם לפניו לטובה לפיכך אם באו לברך בלולב ושופר הרשות בידם:

And they answered: is this generation greater (than previous generations)? Everything that Sarah tells you– listen to her voice (i.e., allow the women to continue their practice), and go say to them "return to your tents! And bless your God!" And the proof (for this) is Ner Chanukah (chanukah candles) and Megillah (Megillah reading on Purim), and they (the angels of heaven) explained to me: That which we find by Megillah and Chanukah, that since [the women] were a part of that miracle, they are obligated in them and make a bracha on them– And by lulav too we find a support for this, that it only has one heart for his Father in heaven[5]. By shofar, too, we find that (the Gemara says:)[6] Hashem says "say before me (the brachot of) Malchiyot (‘Kingship’; this is a section of the mussaf prayer on Rosh Hashanah) in order that you will coronate me over you as king, and (say before me) Zichronot (‘Remembrances’; this is also a section of the Mussaf prayer on Rosh Hashanah) in order that the remembrance of your ancestors should come before Me for good. And with what (does this remembrance come before Me)? With (the blowing of) the shofar.”

Before we get to how the later poskim deal with the above teshuva (responsum), we will make a few comments on its content:

The implication of the beginning of the teshuva is that there was already a longstanding practice for women to make a bracha on shofar and lulav. The teshuva is just coming to justify this practice.

From the wording of the question, we see that the minhag was to have someone else– probably the man blowing the shofar– make the brachot for the women hearing the shofar. There is a disagreement among the rishonim whether this is permitted (if he had already performed the mitzva himself) even according to those who allow women to make the bracha themselves. See Rama (Orach Chayim 589:6) and Bet Yosef and Darchei Moshe there, who says that only the women themselves may make such a bracha, while the Darchei Moshe quotes the Raavya as saying that if the woman can’t make the bracha herself, someone else can make the bracha for her. (See אור חדש- תשלום בית יוסף on Orach Chayim 589:6 who quotes opinions of Rishonim on both sides of this issue.)

However, the שׁוּ"ת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם doesn't clearly answer whether someone else can make a bracha for the women (seemingly the question was about a person who had already performed the mitzva). All it discusses is the women making the bracha. So it’s not entirely clear whether it rules on this issue. (See the following paragraph for more discussion on this point.)

The Darchei Moshe gives 2 reasons for his ruling: it really would be preferable even for Ashkenazi women to follow Maran and not make a bracha on shofar, so even though we don’t protest against their practice to make a bracha, we don’t encourage it by making the bracha for them. (According to this, if a woman asks what the correct way to act on this matter is, the answer would be that she should not make the bracha). The other reason he gives is that since it’s not an obligation for the women to make the bracha, there’s no עַרְבוּת (“joint responsibility”[7], which allows one to perform a mitzva on someone else’s behalf) for the man to make the bracha. The שׁוּ"ת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם would not agree with Rama’s first reason, since it holds that women may certainly make such a bracha. However, it’s possible that it agrees with his second reason.[8]

The main argument of the שׁוּ"ת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם is that the reason women are allowed to make a bracha on the mitzvot of lulav and shofar, is because the reasons behind these mitzvot are relevant to women as well. My impression is that this is not the logic behind most of the poskim who allow women to make brachot on mitzvot that they are exempt from. Rather, there is a general assumption that whenever the Torah gives a mitzva for men to perform, women are automatically included in the ability to fulfill this mitzva (despite not being obligated in it) and even to make a bracha on it. For example, the discussion of Tosfos (Chullin 110b, ד״ה טלית שאולה) and the Rosh (Chullin 8:26) about making a bracha on a borrowed טַלִּית seems to assume that the main criterion for making a bracha on an optional mitzva is whether there is someone who is obligated in it.[9] The Magen Avraham 14:5, the Mishnah Berurah 14:9, and the Kaf HaChayim Orach Chayim 14:14 bring the words of Tosafot and the Rosh and would therefore seem to accept this assumption.[10]

Even Maran the Shulchan Aruch, who holds not to make a bracha, would seem to agree that the actual מִצְוָה קִיּוּמִית (optional mitzva) exists even without the reasons behind the mitzva being relevant to women.

It’s unclear whether the שׁוּ"ת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם meant by his words that women wouldn’t even be fulfilling a מִצְוָה קִיּוּמִית, or just that a bracha shouldn’t be made on such a mitzva (which after all was the question that was asked by Rabbenu Yaakov).

Even the possibility of women not being able to fulfill a mitzva at all (even without a bracha) without the reason behind the mitzva being relevant to them, would seem to have support from some אַחֲרוֹנִים (later poskim)-- Rav Pealim Sod Yesharim 1:12 (about several mitzvot), Ben Ish Chai Shana Rishona Lech Lecha 13 (about צִיצִית) Kaf HaChayim Orach Chayim 17:5 (about צִיצִית), Kaf Hachayim 38:8 (about תְּפִילִּין), Or Letzion 3:4:1 (about בִּרְכַּת הַלְּבָנָה), and see also Chida (about בִּרְכַּת הַלְּבָנָה) in Machazik Bracha 426:4 at the end of his discussion[11]. These poskim seem to assume that when there’s a specific reason why a certain mitzva isn’t relevant to women, then they should not do the mitzva (even without a bracha).

Later Poskim’s discussions of using this ruling of שׁוּ"ת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם

Rav Ovadia Yosef has a long series of teshuvot (Yabia Omer Orach Chaim 1:29-42) on the topic of women making brachot on mitzvot from which they are exempt. In the midst of his discussion he mentions the Chida we mentioned earlier who rules based on this שׁוּ"ת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם that women can make a bracha on the mitzva of lulav.

He dedicates an entire tshuva in that series (siman 41) to the issue of whether we can rely on the halachic rulings of שׁוּ"ת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם.

Proof from the Gemara for the halacha of "לֹא בַשָּׁמַיִם הִיא"

Rav Ovadia (Yabia Omer 1:41:1) goes through many of the Gemaras that say we can’t rely on halachic rulings from heaven:

Eruvin 40a– When David Hamelech asked Hashem whether he should fight the Pelishtim, the Gemara asks what was David trying to ask Hashem? It considers the possibility that the question was whether it was forbidden or permitted for him to go to war (as Rashi explains, it was on Shabbat), and then rejects this possibility, because they could have asked Shmuel and his בית דין. As Rashi explains, we don’t ask Hashem through the אוּרִים וְתֻמִּים (this was a way of asking questions from Hashem)[12] whether something is assur or muttar.

Temurah 16a– The Gemara says that 3 thousand halachot were forgotten in the days of mourning for Moshe Rabbenu. The people asked Yehoshua: “Ask Hashem to tell you these halachot!” Yeshoshua responded: “לֹא בַשָּׁמַיִם הִיא”-- the Torah is not in heaven.

Shabbat 108a– The Gemara says that regarding the question of whether tefillin may be written on fish leather[13], we should ask Eliyahu Hanavi. The Gemara then goes ahead to discuss what exactly we are asking Eliyahu about– and all the possibilities raised are מְצִיאוּת questions (questions about the physical properties of fish leather), not halachic questions. Rashi notes this point and explains that we wouldn’t ask Eliyahu halachic questions, because of the above-mentioned rule of “לֹא בַשָּׁמַיִם הִיא”.

However, the most relevant Gemaras seem to be these 2:

Bava Metzia 59b– The Gemara tells a whole story of how R’ Eliezer proved his halachic opinion from a בַּת קוֹל (a voice making a proclamation from heaven), and how R’ Yehoshua (and the story continues to say that the Rabbis acted based on R’ Yehoshua’s opinion– seemingly they agreed that we don’t follow a בַּת קוֹל.)

Eruvin 13b– The Gemara says that after בֵּית שַׁמַּאי (the Bet Midrash of Shammai) and בֵּית הִלֵּל (the Bet Midrash of Hillel) arguing for 3 years whether the halacha follows בֵּית שַׁמַּאי or בֵּית הִלֵּל, a בַּת קוֹל came out and said: “אֵלּוּ וָאֵלּוּ דִּבְרֵי אֱלֹהִים חַיִּים הֵן, וַהֲלָכָה כְּבֵית הִלֵּל.” “Both of these are the words of the Living God, but the halacha is like Bet Hillel’s opinion.”

Yevamot 14a– The Gemara here discusses people who used to follow the opinion of בֵּית שַׁמַּאי, and considers the possibility of them following him even after a בַּת קוֹל. (The Gemara makes a similar point in Pesachim 114a, Brachot 52a, and Chullin 44a.) Tosafot in Yevamot 14a (ד”ה רבי יהושע היא) asks why do we follow the בַּת קוֹל of Bet Hillel and not the בַּת קוֹל of R’ Eliezer?

Tosafot gives 2 answers:

Since R’ Eliezer explicitly requested for a proof from heaven, we assume the בַּת קוֹל came just for R’ Eliezer’s honor. But it’s not a proof as to what the halacha is. But otherwise, we would follow a בַּת קוֹל.

When there’s a majority of rabbis who follow one opinion, we ignore a בַּת קוֹל which says otherwise.

However, Tosafot admit that these חִילּוּקִים (differentiations) given are only meant to explain what the majority of the rabbis held. But R’ Yehoshua himself clearly holds that we never follow rulings from heaven. This is based on all of the gemaras mentioned above which quote R’ Yehoshua’s opinion in regards to not following Bet Hillel’s rulings from a בַּת קוֹל.

However, Rav Ovadia points out (Yabia Omer 41:23) that the plain meaning of Rambam Hilchot Yesodei HaTorah 9:4 is not like any of the differentiations that Tosafot makes. Rather, we never follow rulings made in heaven.

The Chida (שם הגדולים מערכת גדולים מערכת י ערך רבינו יעקב החסיד מספר 224) goes at length to show that when there’s a serious possibility that either opinion in poskim is correct– since there are good proofs for both opinions– a ruling from heaven should be used to decide which should be followed practically. He also assumes that Rabbenu Yaakov used שׁוּ"ת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם in this way, and actually relied on its ruling.

However, Rav Ovadia points out (Yabia Omer 41:18-21) that this was not necessarily the intention of Rabbenu Yaakov, since it’s very possible that Rabbenu Yaakov didn’t completely rely on the rulings of the שׁוּ"ת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם– rather he himself thought the ruling was correct, and only used the שׁוּ"ת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם to support his rulings. (Either he already thought the ruling was correct, or after seeing the teshuva he realized it was correct.)

In the new edition of Yabia Omer, in footnote 14, Rav Ovadia quotes that Rav David Pardo in ספרי דבי רב פרשת ראה פסקא י דף ר סוף עמוד ד says that really Rabbenu Yaakov already knew the answers to his questions that he asked from heaven, and he only asked to be be sure he was correct, and if the answer would be against what he originally held, he would relearn the topic and see if he would change his mind on his own. This is similar to what Rav Ovadia himself said above.

More discussion of the poskim about relying on שׁוּ"ת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם

Teshuvot Yein HaTov 1:28 argues based on the conclusion of the Chida we discussed earlier, that we can rely on the שׁוּ"ת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם for another case too: to rely on the lenient opinion to allow one קָטָן (boy under 13 years old) to be a part of a minyan for דְּבָרִים שֶׁבִּקְדוּשָּׁה. Even though Maran in Shulchan Aruch Orach Chayim 55:4 rejects this opinion, Yein Hatov argues that since we find in שׁוּ"ת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם that we can rely on this opinion, we can allow it.

Mishpetei Uziel 8:7 responds to the argument of Yein Hatov by pointing out, similar to Yabia Omer, that we can’t rely on the rulings of שׁוּ"ת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם. He then goes ahead to add more reasons why even the Chida would agree that in this case we can’t rely on this ruling:

It’s against an accepted halacha (not a case where there’s an equal doubt as to which opinion is correct). Even the Chida admits that if a posek’s opinion is against שׁוּ"ת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם, he isn’t supposed to follow it. So here where the poskim reject this opinion, we shouldn’t follow it just because שׁוּ"ת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם agrees with it.

The Chida was using שׁוּ"ת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם to defend an existing minhag. (Seemingly this is similar to the previous point.) Furthermore, the שׁוּ"ת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם itself was explicit that it was coming to defend the minhag. (I’m not sure how this makes a difference– in a case where we’d ignore the rulings of שׁוּ"ת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם, I don’t see why the tshuva saying to follow a minhag makes it more reliable.)

In the Chida’s case, the שׁוּ"ת מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם gives a reason why it makes sense for women to be connected to the mitzvot of shofar and lulav, and this reason is a new reason which Maran didn’t see, it’s reasonable to assume that he would follow it if he saw it.[14]

[1] Medieval rabbis

[2] Medieval rabbis in France and Germany, whose teachings are used in the תוספות commentary on the Gemara.

[3] The words of the Radvaz are quoted by the Kaf Hachayim (Orach Chayim 112:3).

[4] Based on text of the tshuva from the Königsberg 1858 edition.

However, this is how this tshuva appears in the edition of Rav Mordechai Goldstein, בהוצאת אורות יהדות המגרב, לוד, תשע”ז:

שאלתי על הנשים שמברכות בלולב, ועל מי שמברך בתקיעת שופר לנשים, אם יש עבירה בדבר, ואם הוי ברכה לבטלה אחרי שאינן מצוות אם לא.

והשיבו, וכי אכשיר דרי, כל אשר תאמר אליך שרה שמע בקולה, ולך אמור להם שובו לכם לאהליכם, וברכו ה׳ אלקיכם, והעד מגילה וחנוכה. ופירשו לי מצינו במגילה וחנוכה שמאחר שהיו באותו הנס חייבות בהם ומברכות עליהם, בלולב נמי שבא לומר שאין לו אלא לב אחד, כך ישראל אין להם אלא לב אחד לאביהם שבשמים, ובשופר נמי אמרי׳ שאמר הקב"ה, אמרו לפני מלכויות שתמליכוני עליכם, זכרונות שיבא זכרונכם לטובה, בשופר. הנשים נמי צריכות שיבוא זכרונם לטובה לפניו, ואם באו לברך בשופר הרשות בידם:

[5] This is based on the words of the gemara in Megillah 14a regarding the generation of Devorah:

וְאִמְרוּ לְפָנַי בְּרֹאשׁ הַשָּׁנָה מַלְכִיּוֹת זִכְרוֹנוֹת וְשׁוֹפָרוֹת. מַלְכִיּוֹת — כְּדֵי שֶׁתַּמְלִיכוּנִי עֲלֵיכֶם, זִכְרוֹנוֹת — כְּדֵי שֶׁיַּעֲלֶה זִכְרוֹנְיכֶם לְפָנַי לְטוֹבָה, וּבַמֶּה — בְּשׁוֹפָר.

And recite before Me on Rosh HaShana verses that mention Kingships, Remembrances, and Shofarot: Kingships so that you will crown Me as King over you; Remembrances so that your remembrance will rise before Me for good; and with what will the remembrance rise? It will rise with the shofar.

וְאִמְרוּ לְפָנַי בְּרֹאשׁ הַשָּׁנָה מַלְכִיּוֹת זִכְרוֹנוֹת וְשׁוֹפָרוֹת. מַלְכִיּוֹת — כְּדֵי שֶׁתַּמְלִיכוּנִי עֲלֵיכֶם, זִכְרוֹנוֹת — כְּדֵי שֶׁיַּעֲלֶה זִכְרוֹנְיכֶם לְפָנַי לְטוֹבָה.

And recite before Me on Rosh HaShana verses that mention Kingships, Remembrances, and Shofarot: Kingships so that you will crown Me as King over you; Remembrances so that your remembrance will rise before Me for good.

[7] Definition from The Laws of B’rachos, by Rabbi Binyomin Forst, page 110. See Chapter 3 Section III for more on this halacha of עַרְבוּת.

[8] ומענין הנ"ל, יש להקשות על דברי המשנה ברורה בזה דסתרי אהדדי, דהנה המשנה ברורה בביאור הלכה קצ:ד ד"ה יטעום כתב בענין לברך על כוס של ברכה של ברכת המזון אע"פ שאין המברך טועם ממנו כלל, אלא הוא מברך ונותנו לאחר לשתות, כמו שסתם מר"ן שם. והביא שרעק"א שם הקשה על זה, דכיון דקי"ל דברכת המזון אינה טעונה כוס, לא הוי ברכת המצוה שאומרים בו אע"פ שיצא מוציא (והיינו שאין בזה ערבות). ותירץ על זה הביאור הלכה, דכיון דלכו"ע הכוס של ברכה הוי עכ"פ מצוה מן המובחר, שפיר אומרים בו אע"פ שיצא מוציא. ובסו"ד שם הקשה על עצמו מפּסק הרמ"א הנ"ל דמי שכבר יצא מצות תקיעת שופר אינו יכול להוציא אשה בברכתו. ותירץ דשאני התם דאין רמז בש"ס שיש שום מצוה בזה, ואדרבה היה יותר טוב שהנשים לא יברכו כלל, אלא שאין למחות בידן, ועכ"פ אין לברך להן מטעם זה וכמו שכתב הדרכי משה.

וכנראה שהוא נקט לעיקר כטעם זה של הדרכי משה, שמדינא אינו ברור שנשים יכולות לברך על תקיעת שופר, אבל אי הוה פשיטא לן דמברכות, שפיר דמי להוציאן בברכה זו. וזה דלא כסברא האחרת של הדרכי משה שם שכיון שאינן חייבות אין בזה ערבות.

ואילו בהלכות הבדלה כתב המשנה ברורה רצו:לו שאע"פ שיש פוסקים שהכריעו שנשים חייבות בהבדלה, וממילא אף אם האיש כבר יצא ידי חובתו בהבדלה, מ"מ יכול להוציא אשה בהבדלה, מ"מ מסיק המשנ"ב דאין להכניס את עצמו בספק ברכה (דדילמא הנשים פטורות מהבדלה), מאחר שיש דרך אחרת שאינו נכנס לספק הנ"ל, שהאשה תבדיל לעצמה, ויכולה לעשות כן כדין כל ברכה על מצות עשה שהזמן גרמא.

ולכאורה זה דלא כסברת הדרכי משה הנ"ל, דהטעם שלא לברך לנשים הוא משום שמא אינן רשאות לברך בעצמן, דהכא המשנ"ב מורה ובא דיש לאשה לברך לעצמה (משום דאפשר דהיא חייבת בה), וא"כ מאי שנא האיש שמוציא את האשה מהאשה עצמה? אלא נראה מזה שחשש לטעם האחר של הדרכי משה, דכיון דאינה מחוייבת בברכה זו אין בו ערבות.

וא"כ לכאורה ב' פסקי המשנ"ב סתרי אהדדי, דבכוס של ברכה פסק דאפי' מצות רשות חשיב מצוה כדי שנאמר בו אע"פ שיצא מוציא, ואילו לענין הבדלה פסק דאם כבר יצא, הוי ברכה לבטלה להצד שנשים פטורות מהבדלה, וזה אפי' להצד שאין איסור לאשה לברך לעצמה.

ואפשר שיש לומר בזה כמו שכתב בחזון עובדיה שבת חלק ג עמוד עד ועמוד תכ בסוגיות אחרות לגמרי, דמי ששנה זו לא שנה זו, וכמו שהעיר בנו של החפץ חיים ב"מכתבי חפץ חיים" עמוד מג, שהוא כתב חלק מהמשנ"ב.

ואולי הביאור הלכה יחלק בין מה שמפורש בגמ' כמצוה (מן המובחר) ובין מה שאין לו מקור בש"ס, שאף להפוסקים שרשאות לברך, מ"מ אינו מצוה ממש שיש בו מעלה אם עושות כן, אלא הוא נֵטרָלִי– שאין בו מעלה או חסרון. ובפרט יש לומר כן לפי הצד שמברכות כדי לתת נחת רוח לנשים, עיין מש"כ בזה ביביע אומר או"ח לט:ז. (אלא שיש לציין שלפי מש"כ שם, לפי סברא זו אי אפשר לסבור שנשים מברכות בדעת מר"ן שאיסור ברכה לבטלה הוא מדאורייתא, ואילו החיד"א פסק שמברכות ואעפ"כ הסכים שברכה לבטלה מדאורייתא, וכמו שהביא ביביע אומר שם אות ז. וגם מדברי השו"ת מן השמים נראה דס"ל דהוי מצוה לענין שופר ולולב.) אלא שיש לעיין אם שיטה זו קאי למסקנת הפוסקים שהמשנ"ב נגרר אחריהם, וצ"ע. ויש יש לעיין אם לשון הביאור הלכה שם יתפרש כנ"ל, שיש בזה ב' טעמים שלא להוציא נשים בברכת השופר– משום שאינו מצוה וגם משום שאפשר שאין רשאות לברך, או דלמא כוונת הביאור הלכה לומר רק ענין אחד– שאפשר שאינן רשאות לברך בעצמן. וא"כ קמה וגם נצבה הסתירה במשנ"ב הנ"ל. וצ"ע.

[9] (Although it is possible to understand that their underlying assumption is that everyone under discussion is relevant to the reason behind the mitzva, the plain meaning of their words is that this isn’t a consideration at all.)

[10] עיין עוד מש"כ בענין זה הרב בצל החכמה (חלק ד, בסוף הספר עמ' רע, השמטות והערות מאת המחבר, לסי' כ"ה אות ב' ח' ט'), ולפי דבריו ודאי אין צורך להיות "שייך" להמצוה מסברא, ודו"ק.

[11] אמנם לענין קידוש לבנה כתב הרב פעלים חלק ד או"ח סימן לד ד"ה ועל שאלה הששית (צויין באור לציון הנ"ל) דאין לזה מקור בדברי האריז"ל. ובאמת המעיין בדברי השל"ה בפנים יראה דלא נתכוון השל"ה לומר שאין לנשים לברך, אלא הוא מסביר למה אין רוצות לברך בתורת רשות. ואין ברור שהחיד"א רב פעלים ואור לציון ראו דברי השל"ה בפנים אלא ממה שהעתיק המג"א סי' תכו בקיצור. (ואע"ג דהרב פעלים העתיק דברים אחרים מהשל"ה, אפשר שלא ראה דברי השל"ה שהובאו במג"א, ואין בזה קושיא למה לא עיין בו, דבלא"ה אין לו מקור באריז"ל ומסתמא לא הסכים לו לדינא.

[12] See Rashi on שמות כח:ל.

[13] This actually exists.

[14] The Mishpetei Uziel gives a proof which is difficult to understand: The Gemara in Kiddushin

34a explains why women are obligated in the mitzva of mezuza:

"דכתיב: למען ירבו ימיכם, גברי בעי חיי, נשי לא בעי חיי?"--

Since women, too, need life, they are included in the mitzva of mezuza, which the Torah says about it that it’s in order to lengthen your life.

This proof is difficult to understand, because by mezuza the Gemara says women are actually obligated based on the reason for the mitzva. This is certainly not true by shofar and lulav!

Seemingly the Mishpetei Uziel just meant to use this to show that women’s connection to the reason of the mitzva can affect the halacha. Therefore, it’s not so farfetched to say that women should be able to perform these mitzvos to the fullest extent, which includes making a bracha. (However, this proof is still far from convincing.)